Eric L. Piza

Evidence Base: Criminal Justice Research, Policy and Action (2026)

Key Takeaways

- Evidence-based policing must evolve beyond “what works” to provide more value to police practitioners

- Innovation is constrained by the growing “burden of knowledge” that typifies developed sciences

- Further innovation requires deeper and more resource-intensive research to generate meaningful advances

- The real-world impact of evidence-based strategies depends more on implementation quality, organizational capacity, and local context than on program design alone.

- Sustaining evidence-based policing requires investment in a broader knowledge infrastructure that integrates evaluation, implementation science, and officer-level data into routine decision-making

Research Summary

This essay argues that evidence-based policing (EBP) has reached a critical inflection point. Decades of rigorous research have clarified which policing strategies can reduce crime, but this success has also produced new challenges. The accumulation of knowledge has created a “burden of knowledge,” making further innovation harder and leaving many aspects of policing practice poorly understood. I contend that the next phase of EBP must move beyond asking what works and focus instead on how, why, and under what conditions policing strategies succeed or fail.

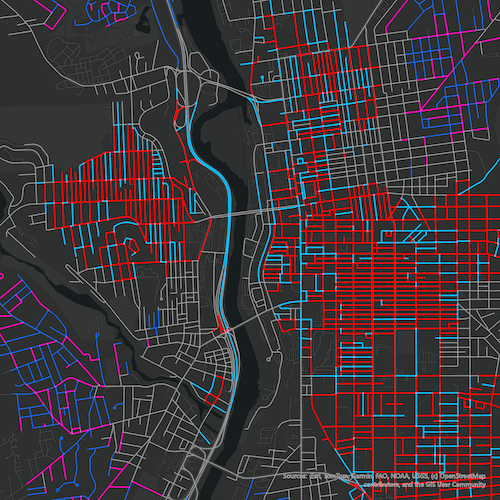

Research has consistently shown that proactive strategies outperform reactive ones, that focusing resources on high-risk places and people is more effective than spreading them broadly, and that problem-oriented approaches outperform generic enforcement. Systematic reviews now provide strong evidence supporting strategies such as hot spots policing, problem-oriented policing, and focused deterrence. As a result, policing is no longer a low-information environment.

Ironically, this growth in evidence has widened the gap between research and practice. Police agencies often struggle to implement evidence-based strategies effectively, even when strong evidence exists. The “burden of knowledge” mechanism explains that as a field matures, advancing it requires greater effort and more complex forms of inquiry. In policing, what police leaders increasingly need is guidance on implementation, adaptation, organizational capacity, and local context.

The essay does not argue for abandoning rigorous impact evaluations. Rigorous designs remain essential for determining effectiveness. However, an exclusive focus on causal outcomes risks stifling innovation by privileging a narrow set of research questions and methods. Further advancement requires a second generation of evidence-based policing built on a broader knowledge infrastructure.

A second-generation EBP should have three priorities.

First, implementation science is essential for understanding how evidence-based practices are adopted, adapted, and sustained in real-world agencies. Factors such as leadership, organizational culture, resources, officer motivation, and external pressures strongly shape outcomes and must be studied systematically.

Second, EBP must better track officer activity. Without knowing what officers actually do on the street, agencies cannot determine whether outcomes reflect strategy design or execution. Technologies such as body-worn cameras and automated vehicle locators provide unprecedented opportunities to study officer behavior, treatment dosage, and police–community interactions.

Third, scholars should better embrace basic and descriptive research. Exploratory, diagnostic, and qualitative studies often generate the foundational knowledge that enables innovation, even if they rank lower on traditional methodological hierarchies.

In conclusion, evidence-based policing stands at a pivotal moment. The easy questions about what works have largely been answered, but the harder work of understanding how policing functions in practice remains. Addressing this challenge requires embracing methodological diversity and treating implementation, context, and officer behavior as central to evidence-based policing’s future.